By J. David Patterson

NOTE: The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of SMA, Inc.

The “Pre-Decisional” draft Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) developed by the Trump Administration is thoughtful and addresses threats to the U.S. as they are. The draft NPR obtained and published by the Huffington Post establishes in the introduction that the world that might have seemed on the edge of security from nuclear conflict, today realistically shows no evidence for such optimism. Despite U.S. leadership to reduce the numbers of nuclear weapons, the “world is more dangerous, not less.” The U.S. has had successful nuclear disarmament initiatives as far back as the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and more recently the 1988 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, the 1993 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty II, the 2002 Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty, and the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty ratified by the U.S. in 2010. However, according to the Secretary of Defense’s preface to the latest NPR, Russia and China have determined in it is in their interest to move away from these agreements. Secretary Mattis describes it this way:

This NPR not only addresses the nuclear threat emerging from historical competitors, but relatively new adversaries, as well. To that end, the Secretary points out:

It is clear in the Trump Administration’s pre-decisional draft NPR that these threats are a change in the global nuclear arms landscape. The deterrence impact of “mutually assured destruction” (MAD) was coined by Donald Brennan, a strategic researcher at the Hudson Institute in 1962, and proposed as strategic military doctrine that same year by President John F. Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara. In a speech before the American Bar Foundation, McNamara explained MAD as “flexible nuclear response.” His point was that by stockpiling a vast number of strategic nuclear weapons, there would be enough of an arsenal to withstand a first nuclear strike and annihilate totally an adversary. Consequently, with absolute certainty that an enemy (read Soviet Union) would not survive and no such enemy would attempt a first strike. Today, the idea that MAD is a “flexible” approach to a nuclear standoff is less relevant, if not a non sequitur in any serious discussion. However, much of the thinking that prevailed in the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s regarding the cold war trade-off between tactical nuclear weapons and conventional weapons may still have application for several decades into the future. That is not to say that the Trump Administration is backing away from its commitment to the eventual elimination of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction, nonetheless it does recognize that the threat has become greater in capability and is more pervasive:

During the cold war, the conundrum that the U.S. faced was what to do about the disparity in size of the land forces of the Soviet Union and its advantage in armor versus the smaller NATO force. A Soviet incursion through the Fulda Gap by necessity would have to be met with tactical nuclear weapons. NATO consistently refused to agree to a “no first use” policy. Otherwise, the NATO forces would be overwhelmed. This first use of tactical nuclear weapons would immediately escalate, it was believed, to the use of strategic nuclear weapons. The use of strategic nuclear weapons was unacceptable based on the MAD theory thereby putting the NATO and allied forces facing the Warsaw Pact conventional forces at a stalemate. That is where they stayed for nearly three decades, until the Reagan administration demonstrated that the U.S. could field two intermediate range nuclear missiles in less than three years, while the Soviet Union could manage only one.

But, that was then. This is now. As the new NPR, though “pre-decisional,” states,

Additionally, this new and “unprecedented range and mix of threats” includes potential adversaries’ belief that a first use of and reliance on “nuclear employment” will establish a “useful” competitive advantage in any conflict with America. The NPR identifies Russia as having this mistaken notion in that Russia with its greater advantage in number of “low-yield” weapons can establish an upper hand and intimidating position in a crisis as well as “lower levels of conflict.” This NPR takes on this erroneous idea by explaining,

To achieve this deterrence, the U.S. will continue to pursue equipping the F‑35A (U.S. Air Force variant) with nuclear weapons capability as a dual-capable aircraft (DCA). Furthermore, the United States will begin to modify a small number of existing Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missile warheads with a low-yield option. This will give the U.S. low-yield capability that does not rely on host nations for support.

A departure from the 2010 NPR that committed to retiring the U.S. Submarine-Launched Cruise Missiles (SLCM), the new posture review announces that the U.S. will begin “immediately” to restore the nuclear capability to SLCMs by starting a requirements study that will establish the baseline requirement for an Analysis of Alternatives for “rapid development” a more up-to-date SLCM.

This more realistic approach to nuclear deterrence on the strategic and non-strategic levels addresses a rather stark disproportionate proliferation of a variety of nuclear systems by competitors and adversaries. Since 2010, while the U.S. has begun fielding of one new nuclear capable platform, the F‑35A, adversaries and near-peer competitors are developing or have fielded, 19 ground-based missile systems, nine sea-based nuclear missile systems and four airborne nuclear capable systems. Russia alone,

In 2012, the National Intelligence Council described the comparative trend in Russia’s intentions regarding its nuclear capability vis-à-vis the U.S. this way,

Equally troubling, and a departure from where nuclear competitors stood in 2010 is the rapid emergence of China as a growing nuclear power. The 2018 NPR estimates that if China continues to grow its number, capability, and protection of its nuclear forces, it will be a first tier force by 2050. To that end, China has developed a new “road-mobile” intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), a new multi-warhead version of its silo-based ICBM, and its modern, most advanced ballistic missile submarine armed with modernized SLBMs. Both Russia and China are developing and testing ballistic missile defense systems, while continuing to criticize the U.S. for its missile defense system.

Prominent in today’s news is the North Korean and Iranian nuclear weapons programs. North Korea has greatly accelerated its nuclear weapons and missile capabilities and has explicitly threatened the U.S. with that capability. All indications are that the North Korean threat is the most pressing threat. The 2018 NPR describes it as:

As the nation that is the number one sponsor of Jihadist terrorism, Iran also represents a real and present threat. Despite the limits placed on its nuclear program by the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which will have held Iran’s nuclear ambitions in abeyance for slightly more than a decade, it retains the technology it had before JCPOA. Estimates are that Iran could have a nuclear weapon within one year. Iran’s ballistic missile development program appears to experience no such constraints. A new report reveals that Iran has launched 23 missiles since signing the PCPOA, which most critics of the agreement consider a violation of the deal. As many as 16 of the missiles are reported to be nuclear capable.

Additionally, as rogue states like North Korea and Iran have or are on the cusp of having nuclear capability and exhibit bellicose behaviors, these nations are a real threat, and the U.S. must meet that threat with a nuclear capability that is commensurate with that threat.

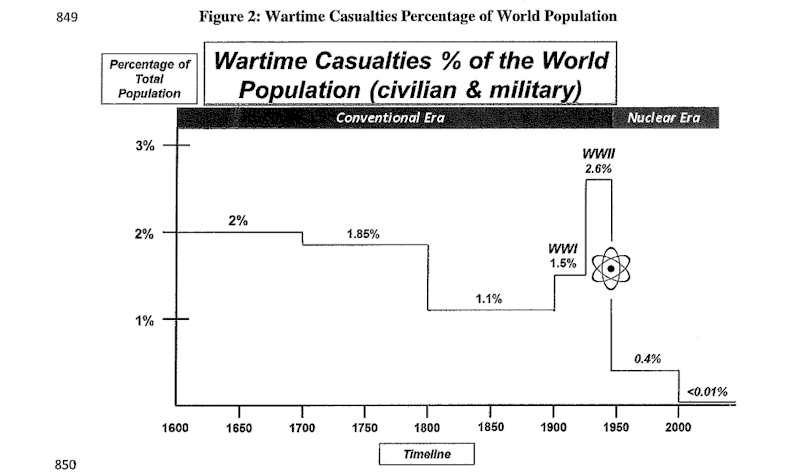

The argument made in the 2018 NPR that I would take issue with, since it comes off as gratuitous, is that global war, the norm prior to the U.S. introduction of nuclear weapons, has experienced a sustained and precipitous reduction based on global war-related lives lost as a percentage of the global population. It is not clear that there is a cause and effect case to be made resting entirely on the U.S. using nuclear weapons during World War II and the subsequent deterrent effect. Many other factors play in the reduction in lives lost to wartime as a percentage of world population. The rapid growth in world population would be one for example. My impression is that the writers had this excellent chart that illustrates that since 1600 through 2000 the number of lives lost to war globally as a percentage of total world population is going down. It seemed a shame to waste it. The fifty years from 1900 to 1950 were of course banner years for humans destroying humans even as the population of the world continued to increase. If the first half of the 20th century is removed as an anomaly, it appears that the percentage of deaths because of global war have decreased as a percentage of population at a steady rate. So, this section attempting to show that the U.S. with nuclear weapons was the cause of a slowdown in human carnage because of global war, is questionable—see the chart below. I would recommend the chart and accompanying narrative be deleted in the final version.

The most significant factor in deterrence is the position that the U.S. takes in declaring that it reserves the right to use nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances, a position made clear with the following statement of policy:

Finally, the 2018 NPR addresses deterrence as it applies to both nuclear and non-nuclear attacks. Threats include chemical, biological, cyber, and large-scale conventional aggression. Any adversary who is determined to attack the U.S., its allies, or its partners, must realize that,

The 2018 NPR goes into significant detail for addressing each of the potential threats that the U.S. faces both nuclear and non-nuclear and what it is prepared now and will be more prepared in the future to do as a hedge against these threats. However, despite the requirement to significantly modernize existing nuclear capability and develop new,

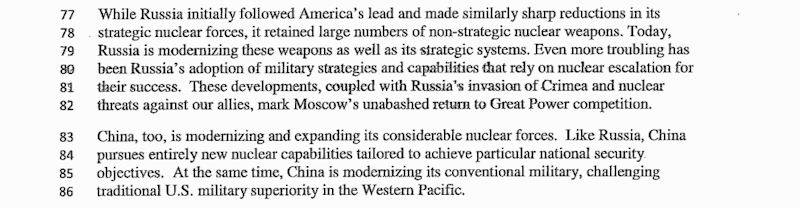

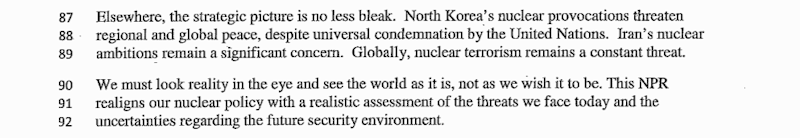

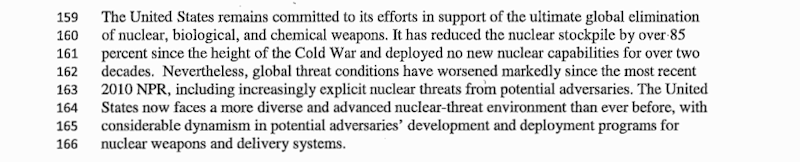

Yet, as the 2018 NPR makes very clear, the U.S. will always be unwilling to put its national security at risk from the present danger of unpredictable and malevolent international adversaries. The 2010 NPR closed with a section entitled, “Looking Ahead: Toward a World without Nuclear Weapons.” As appealing as this sentiment maybe, the world the U.S. faces a short eight years from the 2010 NPR is decidedly more dangerous with both nuclear and non-nuclear weapons in the hands of a wider variety of traditional and rogue nations. The 2018 NPR portrays less cause for optimism and a greater urgency for the U.S. being prepared for a ubiquitous nuclear threat.