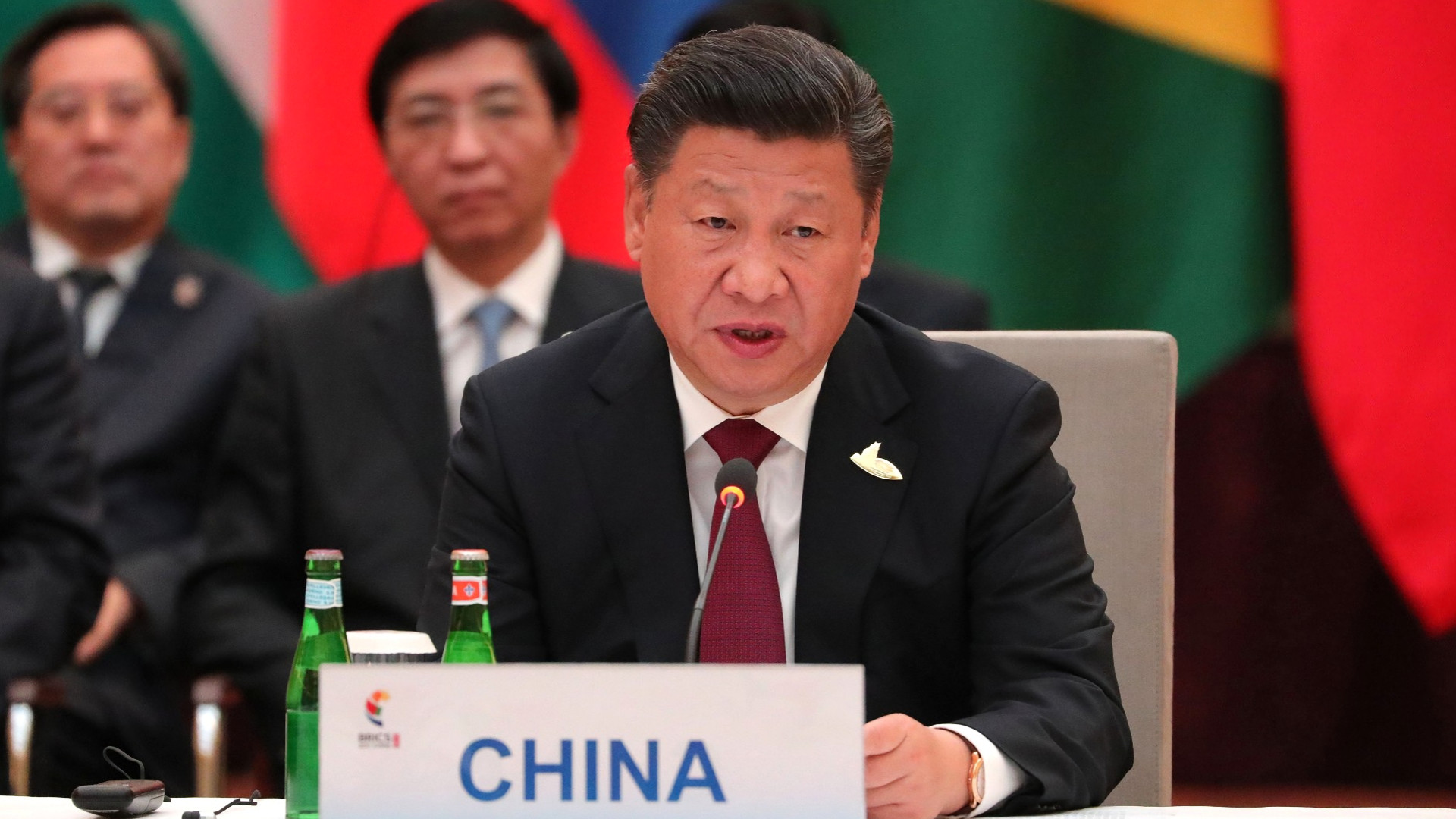

President of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping is hard to parse. He has accumulated honors but also enemies, starting with the Trump administration but extending to domestic elites who have lost riches through the anti-corruption campaign, and officials who feel micro-managed from the center. He has centralized authority to an extent perhaps even greater than Mao but also centralized responsibility for failure if it happens. He understands U.S. politics better than we understand his, but he badly misunderstood what a Trump—as opposed to a Clinton—presidency would mean for China. Yet he will probably emerge the winner from Trump’s trade war with him.

By Gregory F. Treverton

NOTE: The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of SMA, Inc.

As a result, China is a bundle of contradictions that bedevils prediction. Economically, the safest prediction is a continued slowdown but not a crash, yet even that bet is not one on which to risk the farm. Non-performing loans loom as a problem unresolved. It is important to remember, though, that China’s debt is not like America’s debt was in 2008: a housing bubble doesn’t loom; and households are fairly lightly leveraged. Nor is government debt a problem, for most of the debt is on corporate balance sheets. Still, credit booms hardly ever end well. Growing out of debt is the most painless escape, but the rub—another contradiction—is that containing the debt bubble by winding down leverage inevitably will slow growth.

The ability of China, Confucian in culture and nepotistic in practice, to innovate remains the largest mystery about its future, and Xi’s as well. China has gotten rich copying or stealing technology, but now the issue is whether it can move up the value chain by creating technology. That is the aim of the “Made in China 2025” program, a strategic plan issued by Premier Li Keqiang in May 2015 which amounts to a declaration of war for technological dominance. The images of huge government programs, in artificial intelligence for instance, scare us but also evoke Soviet practice, and thus play to our bias that innovation cannot be commanded from the top. Yet the Soviet Union did not do too badly, at least in the military sphere where it concentrated its efforts. More important, China has microchips that the Soviet Union did not—all those technologists educated and seasoned in the West but now tempted to return home by offers of residence in decent cities, with housing to match, and all the labs and graduate students they can manage.

The disappearance earlier this year of China’s most famous actress, Fan Bingbing, is a parable of Xi’s China, a demonstration of very high-tech surveillance in the service of authoritarian control if indeed her disappearance is linked to unpaid taxes. If her case is a parable, that of the Uighurs in western China is a tragedy. Their treatment amounts to an experiment in social control at scale, with perhaps a million people in concentration camps, labeled in Xi-speak, “re-education camps,” suggesting that Xi does not know or does not care about the resonance in other nations’ ears from Soviet or Nazi practice.

Indeed, Xi’s “social credit” scheme is the scariest, most Orwellian authoritarian reach in today’s world. Google may aspire to know everything about your life online. China aspires to know everything about your life, period. Like Google, it records the virtual contrails of Chinese citizens. But it also turns the likes of Facebook “likes” into weapons, encouraging citizens to grade their fellows. Depending on your social credit score, you may turn up at the airport and discover that you’re not allowed to fly to Shanghai, let alone live there.

Yet even the Orwellian spawns a puzzle. Repression mixes with responsiveness. Chinese authorities are in touch with citizens, even in real time, and respond to their concerns. The process has even been called “phantom democracy” (shenjingshi min zhu)—“where the fear of democracy forces a style of political management that in many ways mirrors and mimics electoral democracies, where the fear of elections puts leaders in constant campaign mode.”[1] Chinese authorities carefully listen to public opinion on social media, and engage with the complaints. It is monitoring plus engagement, which might be called “authoritarian deliberation.”[2] Officials are increasingly encouraged, and in some cases required, to set up public profiles on Weibo, China’s version of Facebook, and WeChat, a mobile chat app. The number of official Weibo accounts was more than 137,000 at the end of 2018 and the number of official WeChat accounts was over 100,000. These numbers will likely continue to grow.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—also known as the One Belt One Road (OBOR) or the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road—seems less a strategic plan than an improvised response to over-capacity at home, along with nearly free capital. To be sure, it has a strategic overlay but one that has not always turned out well: witness China’s loans to build a port in Sri Lanka, which then, unable to service the debt, was pressed to lease the port to China, evoking cries of “debt trap.” For similar reasons, Malaysia opted out of BRI.

The main question about BRI is how much of it China can afford. The numbers vary, and since most of the Chinese participants are state-owned enterprises (SOEs), they are also suspect. But China’s commitments are in the tens of billions of dollars, while by one estimate, infrastructure needs in the region run to several tens of trillions. There is already a backlash, as poor regions ask pointedly why the country is spending so much abroad while there is so much to do at home.

Churchill’s description of Russia is apt for Xi’s China, a “riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Perhaps the rest of the quote, less known, is also apt: “…but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.” Nobody wins a trade war, but Xi is likely come out better because Trump acted in pique, with little sense and no analysis of national interest. That calculus of national interest by Xi might, just might, mean that his great initiatives will surprise us by their success.

[1] John Keane, “Phantom Democracy: A Puzzle at the Heart of Chinese Politics, South China Morning Post, 25 August 2018, available at https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/2161276/phantom-democracy-puzzle-heart-chinese-politics.

[2] Maria Repnikova, “China’s ‘Responsive’ Authoritarianism,” Washington Post, November 27, 2018, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/theworldpost/wp/2018/11/27/china-authoritarian/.