States are once more front and center in international politics, after twenty years of scarifying concern about non-state actors, especially terrorists.

By Gregory F. Treverton

Note: The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of SMA, Inc.

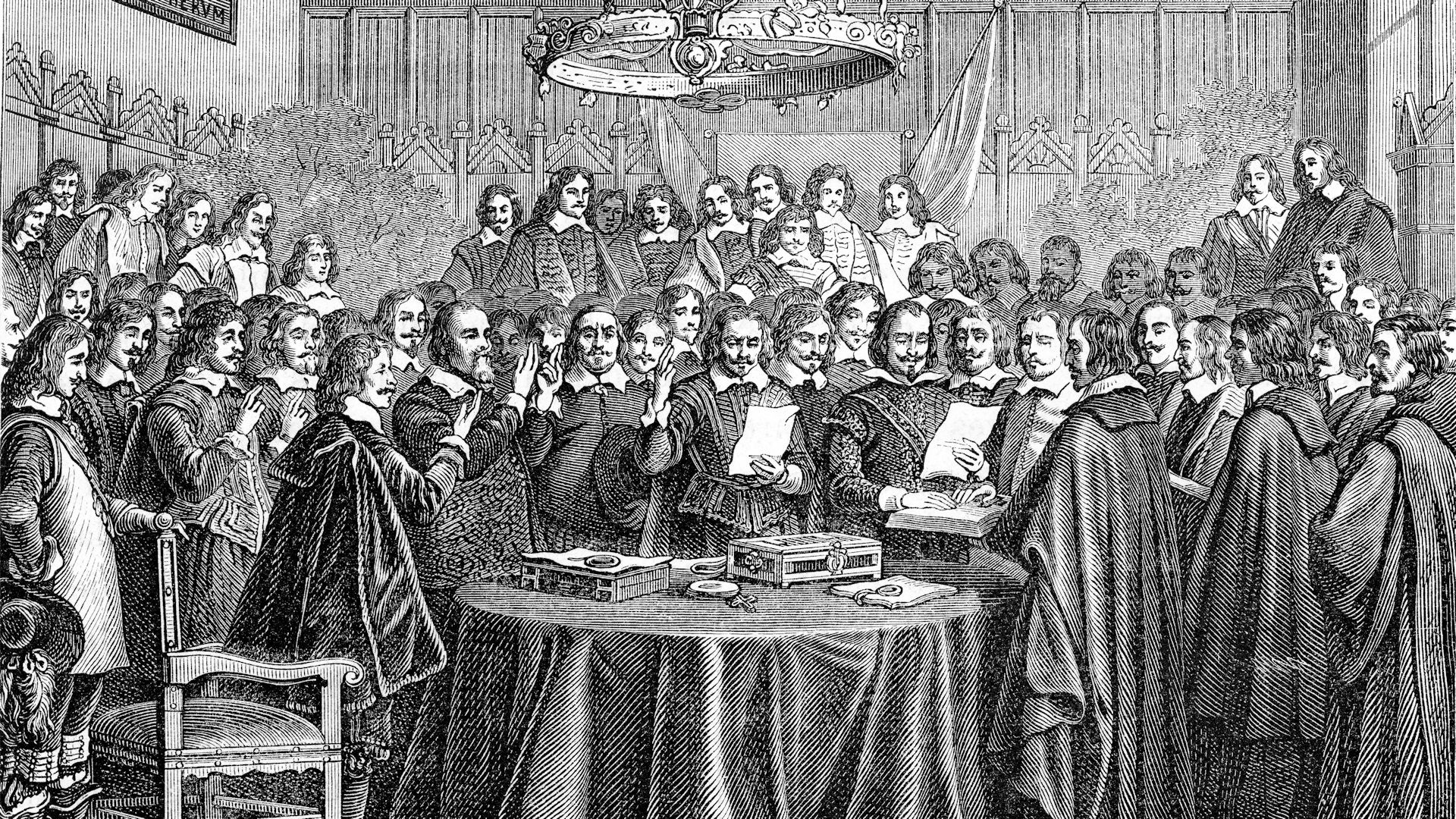

Those nation-states have dominated international affairs for a very long time, for it was the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 that enshrined the principles that form the basis for that state-centric international system: national self-determination, sovereignty, and non-interference in the internal affairs of sovereign states. Yet the history of competitors to the nation-state, from both above and below, is also a long one, and the competition has intensified dramatically in the last several generations, though without displacing the primacy of states.

From above, Westphalia already envisioned not just non-interference but also a balance of power among those sovereign states, a rough kind of what we might now call international governance. From the Concert of Vienna through the League of Nations, the United Nations (UN) and the European Union (EU) states have framed supranational authorities to keep peace and promote prosperity. Now, all those efforts seem in peril. The UN remains gridlocked by the veto power of the five permanent Security Council members, and the EU, built on open borders and the assumption that Europe would be an expanding zone of peace, is mismatched to its current challenges, immigration, and Russian intervention. If anything, it is devolving authority back to nation-states, and even that devolution was not enough to prevent Brexit.

What we too easily called the “liberal international order”—the Bretton Woods institutions, the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and, later, the World Trade Organization (WTO)—also seem not up to the task even as China tries to supplant them with international organizations of its own design. Indeed, economists like Dani Rodrik argue that the “hyperglobalization” around the turn of the last century begat the backlash against globalization precisely because it left nation-states with too little leeway to pursue their own economic interests.[1] It put national economies at the service of the global economy, rather than the other way around.

So, too, the urge to create more nation-states—from the U.S. Civil War to the breakup of the Ottoman Empire and later of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union—also seems alive and well. Among the ironies of Brexit is the incentive it provided Scotland to separate from Britain. And as the red state-blue state divide hardens in the United States, it sadly becomes thinkable that we too might come apart, in practice if perhaps not in formal structure.

Competitors to the nation-state from below also have always existed—think of the “robber barons” of the last century—but are much more visible now. Several decades ago, I and others coined the term “market state.[2] The idea was that while the state wasn’t about to go away, it was being transformed by the force of economics, while our habits of thought and institutions remained powerfully conditioned by the Cold War focus on interstate relations and the balance of power. The state’s role would be transformed from decider and doer to prodder, facilitator, and coalition builder.

Major corporations, which had traditionally been conceived as “rule takers,” operating under regulations set by national government or international organizations, were becoming “rule makers.” They were big and powerful enough to exert control over their operating environments. Now, that is literally true as, for instance, the tech giants decide themselves how to police their platforms. And the scale of private wealth is, literally, mind-boggling. The Gates Foundation spends more on health in Africa than the World Health Organization (WHO), and, while we lack metrics, I daresay Google is a more important international actor than, say, Spain—or pick your favorite middle-sized rich country.

The globe now seems awkwardly poised amid the continuing dominance of the nation-state, the pressure of riches in the private sector, and the need to tend the global commons lest humankind perish in pandemic or climate crisis. It is tempting to observe that, however well or badly the nation-state has served the globe since 1648, its time has passed. One doesn’t have to be a realist theorist in international relations to observe that competition is virtually built into the system of nation-states. During the pandemic, it wasn’t just “America first” but also those European EU partners withholding medical supplies from each other.

Gregory Bateson, the eminent anthropologist, put our existential dilemma piercingly a half century ago:

“If we continue to operate in terms of a Cartesian dualism of mind versus matter, we shall probably also continue to see the world in terms of God versus man; elite versus people; chosen race versus others; nation versus nation; and man versus environment. It is doubtful whether a species having both an advanced technology and this strange way of looking at its world can endure.” [3]

[1] Dani Rodrik, “Globalization’s Wrong Turn: And How It Hurt America,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2019, 26.

[2] “Intelligence and the ‘Market State.’” Studies in Intelligence, 10 (Winter/Spring 2001), 67-76, available at cia.gov/static/99dc6a1a594f107003a00ffd7e532cfc/intel-and-market-state.pdf.

[3] “The Cybernetics of ‘Self’: A Theory of Alcoholism,” in Steps to an Ecology of Mind, University of Chicago Press, 1972, p. 455.