Any confident predictions about China’s future, let alone the Sino-American relationship, are suspect. While anti-Chinese sentiment still spans the US political spectrum, the discussion of China has moved with dizzying speed from worrying about China as an economic superpower to fretting (or gloating) about its economic downturn.

By Gregory F. Treverton

Note: The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of SMA, Inc.

And, as events of the last decade have shown, the future of the United States is at least as uncertain. It is eerie but unsurprising, perhaps, that the two most important powers in shaping the future world order are also the globe’s two most powerful states. So, too, the contrast between the last two American presidents reminds us that China’s leaders have also been very different, from the murderous populist Mao Zedong to the sophisticated reformer Deng Xiaoping. Xi Jinping may be followed by someone quite different.

China and the United States

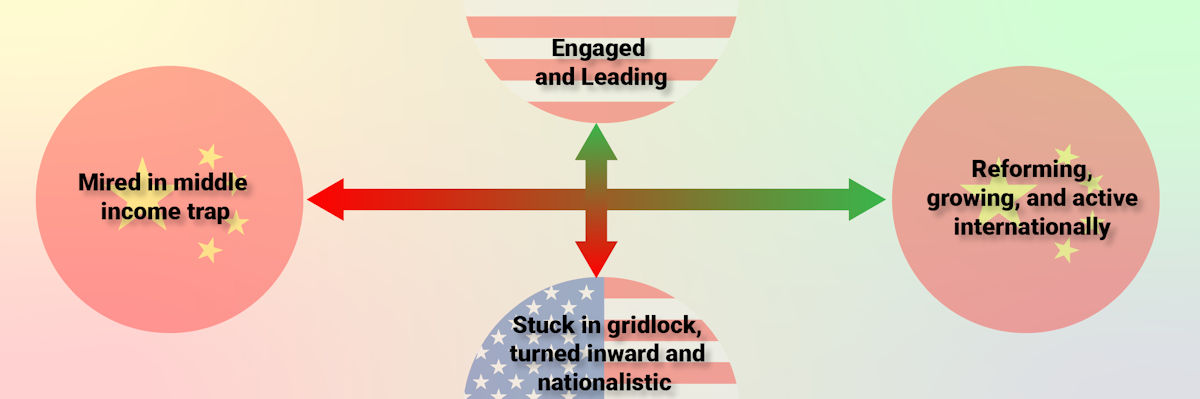

To stretch thought about that future, consider the following scenario exercise. This is the classic style of Shell scenarios, continued by the Global Business Network. [1] Imagine two continuums. One would be China. It would run from reform and growth slowing, and the country not escaping the middle-income trap. “Middle income” is defined by the World Bank as between $1,000 and $12,000 per capita income per year. On an exchange rate basis, China has been in that range for a quarter century. The trap ensues if a country’s wages rise enough to exhaust its potential growth in export-driven, low-skill manufacturing before the country becomes innovative enough to compete against developed countries in higher value-chain economic sectors. Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea remained in middle income for 29, 27, and 23 years, respectively. The issue is contested, but perhaps only one country over 40 million in population has escaped the “trap” since World War II—South Korea.[2]

The other end of that continue would be a China in which reform had continued apace and so had growth, with the trap surpassed. This China would be both a model for many countries in the Global South and rich enough to continue to finance a wide variety of internal ventures, especially its Belt Road Initiative, or BRI.

Notice that while the continuum is defined primarily in economic terms, economics cannot be separated from with politics and policies. For instance, while China cannot reverse its aging population—the workforce peaked in 2015—it can both undo some of the ills of Xi Jinping’s rule and return to other reforms. In the first category would be his attacks on the private sector, especially high tech, in favor of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), or exploding the property bubble so rapidly as to deprive many Chinese of their most valuable asset. The second would be comprised of, for instance, measures to increase consumption, especially increased social welfare spending, in a nation famous for saving.

For the United States, the continuum would run from a country that was stuck in political polarization and gridlock, unable to act decisively, not much interested in global leadership, and not much of a model for any other country. It might be an inconsistent America, one veering sharply from administration to administration, much like the contrast between Trump and Biden. This America would define its interests narrowly, perhaps focused on economics, with a transactional view of foreign relations. Its support for international institutions, including NATO, would also be inconsistent, thus tepid at best.

At the other extreme would be an America that had achieved tolerable consensus in support of an engaged role in the world, one that sought leadership and supported international institutions. No doubt economics would play a role in determining where the country fell on the continuum, but probably less so than for China, given how much richer America is in per capita terms.

The continuums are displayed in the figure below.

Figure 1: Four Scenarios

Four Scenarios for the Future

The two continuums produce four quadrants and thus four scenarios. These are not predictions but rather a way to explore plausible and interesting futures. For each scenario, I suggest implications for the global economy, world order (adversaries and allies) and global security.

A Bipolar World Redux. The upper right-hand quadrant is a happy future for the global economy, with the “clubs” around both China and the United States growing. It would not necessarily presume that China would become more democratic or disposed toward the Bretton Woods international institutions, like the World Bank or International Monetary Fund, but it would be a world in which China shared an interest in an open international economy.

In this scenario, economics would drive cooperation, as would concern over humanity’s future in a world of global warming and pandemic danger. The great uncertainty would be whether that would mute the competition of two bipolar powers. Could the two escape the “Thucydides trap,” the prospect that when a dominant world power is faced with a contender, war is a likely result?[3] It’s tempting to say that trap is too zero-sum a view of the world to provide guidance today when economics dominates global affairs, but earlier observers, like Norman Angell, said that before World War I.[4] Graham Allison’s scholarship is careful, and the historical record is not encouraging: in sixteen cases when rising powers confronted dominant ones, war was the outcome in twelve. And just as surely, the situation is unprecedented in America’s history since we have been the rising power, not confronting one, so we lack a frame for conceiving policy and know that analogies will mislead.

Return to Unipolarity. The world of upper left-hand quadrant would resemble that of the early 1990s, when the Soviet Union had collapsed, and China’s rapid rise was just beginning. It would be a mixed world for the global economy: global growth would be slower without the Chinese engine, and the Global South would be much in the position it was in the 1990s, rather compelled to work with American-led international institutions and practices whether it wanted to or not. The uncertainty in this world would how much of a spoiler China turned out to be. Its nuclear weapons would not have gone away, nor would its size advantage in naval power. As it sought to sustain support for the Communist Party but was less able to do so by rising the economic boats of its citizens, it would be likely to play the nationalist card. That might include more than saber rattling over the status of Taiwan.

Messy Multipolarity. The world of the lower left-hand quadrant would be rather dog-eat-dog, with emphases on national well-being and limited globalization, shortened supply lines and watchful eyes on foreign investment and technology transfer. It would be world of still slower growth that the unipolar one. The Global South would be on its own, seeking the best deals it could with China, the United States and Europe; the United States, as the richer power, would retain some reluctant advantage. In this world, as in the unipolar world, China would have the incentive to play the nationalist card.

China Ascendant. The world of the lower right-hand quadrant would be mixed for the global economy, with slower growth than bipolarity or US unipolarity, given the relative riches of the United States. But China would be the world’s largest economy on all measures, even as it lagged the current rich countries in per capita income. The Global South would tilt sharply toward China, and international institutions would be reshaped accordingly. US allies would be discomfited: some, like Australia, might find the lure of the Chinese economy irresistible while others, Canada, and many European countries, would feel they had little choice but to stick with the United States.

Here, the big uncertainty would be US actions. Would the country gracefully slide into a world in which it no longer dominated the shaping of international practices and institutions? Or would it lash out in anger with instruments ranging from sanctions and economic restrictions to, perhaps, shows of military force?

The scenarios drive home Henry Kissinger’s words: the Sino-American relationship is “the key problem of our time. Each of us is strong enough to create situations around the world in which it can impose its preferences, but the importance of the relationship will be whether each side can believe that they have achieved enough to be compatible with their convictions and with their histories. That is a huge task. It has never been attempted systematically by any two nations in the world.”[5] Let us hope China and American can pull it off.

[1] See Schwartz, Peter Schwartz, The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World (London: Penguin Random House, 1996).

[2] This rests on the conclusion that Japan escaped the trap before the war, and there is room for argument about other countries, in Southern Europe especially. Thus, the trap should be treated as a cautionary speculation, not a hard fact.

[3] Allison, Graham T., Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2017).

[4] Sir Norman Angell, The Great Illusion: A Study of the Relation of Military Power in Nations to their Economic and Social Advantage, (New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1911).

[5] Kissinger, Henry, “The Key Problem of Our Time,” interview by Stapleton Roy, Wilson Center, September 20, 2018, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/the-key-problem-our-time-conversation-henry-kissinger-sino-us-relations.