The cyber realm is too important to be left to the technologists.[1] It is, in a very real sense, the great challenge of our times: we’ve dealt with the overlap of public and private before, but cyber is new in scale in a way that makes it new in kind. Never before have such powerful public interests been almost entirely in private hands.

By Gregory F. Treverton

NOTE: The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of SMA, Inc.

Framing the Challenge

Working across that divide is the critical task for all democracies. However, policymaking on cyber is also bedeviled by two other divides. One is civil-military: is the realm of government responsibility to protect “.gov” or “.com”? The other is offense-defense. For the United States, making policy is complicated because offense is to tightly compartmented that the would-be defenders don’t get to practice against what we hope is the best offense around. These divides have meant that a succession of civilian cyber “czars” has turned into cyber “czardines,” and that, lacking better, the United States has made its signals intelligence service, the National Security Agency, into not just the central cyber institution for the government but for the country as well. In that America is hardly alone: Sweden has gone very much in the same direction and for the same reasons.

Because cyber is only a couple of decades old, we are still working through how to think of it. Conceptually, what is the right frame? Nuclear analogies are tempting but misleading. For one thing, attribution in the nuclear era was pretty straightforward: sure, a bomb could have been delivered to an American port by several powers, but a major attack was only going to come from the Soviet Union. In the cyber realm, attribution is slow at best and imprecise at worst. More optimistically, cyber does not pose the existential threat that nuclear weapons did: any attack also alerts the victim to where it is vulnerable, giving it opportunity and incentive to patch the vulnerability. Notions of “cyber Armageddon” are overblown.

That suggests that biological metaphors may be more apt. Any attack results in antibodies, in a constant contest of infections and antibodies. It is intriguing that our vocabulary is so mixed. “Virus” suggest biology, but “patch” connotes mechanics. Our language demonstrates how are we are from a clear conception.

For policy, the central challenge is that the familiar paradigm will not serve. That paradigm for dealing with risk—from fire to flood to electricity—is regulation as a requirement for insurance. There surely will be calls for regulation, especially in Europe with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). But the policy challenge derives from the fact that the technology moves too fast: today’s regulations will be either dead on arrival or, worse, counterproductive.

That said, the pressures to regulate will only grow, and the Facebooks and Googles, who were caught unawares when they shouldn’t have been, will be whipping boys for a long time. Their business plans mesmerized them—and also the body politics for some time. This tussle will go on for years, and it will shape the cyber realm. Mark Zuckerberg’s performance before Congress in the spring of this year was a perfect illustration of the cluelessness on both sides: Zuckerberg didn’t realize the hole he was in, but his congressional interlocutors were embarrassing in their lack of understanding of what he was talking about. Google and Facebook are caught in an untenable position: they can no longer argue that they are only “platforms,” with no responsibility for the content they purvey, but they are a long way from being either willing or able to be “publishers” fully responsible for what content they carry.

Threats and Lessons from Previous Attacks

The cyber threat falls into three classes. The most familiar is destruction, such as DDoS (directed denial of service) attacks that seek to take down servers and other infrastructure. The Russian attack on Estonia in 2007 is the poster-child for this form of attack. Second is cyber espionage, or exfiltration, breaking into networks to steal information for financial or political gain. Russia’s hacking into both the Democratic National Committee email and that of Hilary Clinton’s campaign manager, John Podesta, before the 2016 U.S. elections is the most vivid recent illustration. Third is manipulation, that is, breaking into a target’s data with the intent of changing it, perhaps well before the victim is aware. That seems the next big frontier of cyberattacks.

My experience on the inside of government and intelligence was instructive about these attacks. All the major ones were in the second category—cyber espionage to exfiltrate damning information. For the first major hack, the one by North Korea into Sony, we had a combination of good luck and good work that produced very reliable attribution very quickly. Not so for the bigger and still more dangerous hack into the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), which compromised the security records of more than 20 million Americans (including my own). In that case, we fairly easily could say the hack came from China but found it difficult to be more specific. To our demanding policy counterparts, we were more or less in the position of saying “China is a big place.” I did think, though, that the delay was instructive for our policy counterparts because quick, determinative attribution will be the rarity. (Donning a policy hat, I also have to say that I didn’t mind some delay because the retaliatory options seemed so unattractive.)

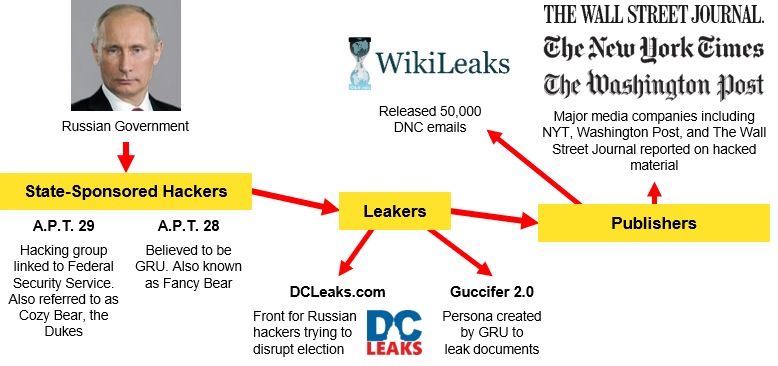

The Russian intervention in America’s 2016 elections was a dramatic illustration of “hybrid threats” and of the new tools in the attackers’ toolkit—cyberattacks and social-media aided propaganda. It is worth noting that both are relatively cheap and perhaps hard to attribute. Compare the cost and difficulty of inserting an article into a newspaper during the Cold War with the cheap ease of having a troll post fake news and then lots of bots making it appear to be trending. With both the hacks and propaganda, the Russian mode of operations was similar: Russian intelligence services created personas, DCLeaks and, Guccifer 2.0, to release the hacks, and did the releases at strategic times—at the end of the Democratic convention and on the day the news broke of Trump’s groping of women. The goal was to control the news cycle and distract attention from either Ms. Clinton’s triumph or Mr. Trump’s foibles. For social media-aided propaganda, the goal was the same: to use bots to make it seem as though fake news, such as of candidate Clinton’s ill health, was trending and thus get it picked up by mainstream media.

Figure 1 illustrates the process:

Figure 1: From Hacks and Propaganda to Mainstream Media

Guidelines for the Future

The sequence of Russian interventions in elections in the last several years is both instructive and suggestive of possibilities. The intervention in the U.S. elections came as a surprise, though it shouldn’t have. As early as 2014 a private group examining jihadist web-sites discovered anomalies—like “Free Syria” posts that weren’t Syrian—that pointed directly at Russia. They tried to warn the U.S. government, but at that point it was interested only in jihadists, not Russians. However, by the time of the French elections in 2017, the French, not to mention the world, were alert to Russian behavior, and the Macron campaign was on the look-out for it. It carefully monitored what the Russians were doing and even managed a counter-attack of sorts, flooding addresses from which spearphishing emails were coming in an effort to distract and overwhelm the phishers.

Intriguingly, by the time of the German elections later that year, there is no evidence that the Russians intervened at all. They may have calculated that they didn’t need to, that events in Germany were unfolding to their advantage in any case. But it may be that they realized they had overplayed their hand, and that if they intervened, their intervention would be the big news, not the fake news they sought to purvey.

It is useful to think of the options in cyber defense as a range:

- Prevention

- Deterrence?

- Attribution

- Remediation

- Retaliation?

For a private sector company, the first two options may amount to much the same thing: like two hunters being chased by a bear, each hunter doesn’t have to outrun the bear, only the other hunter. So better cyber security than competitors encourages the bear to go after the other hunter. Deterrence is a much harder issue for governments, perhaps especially the United States because it is so dependent on the cyber realm. So, too, attribution may be less important to the private sector unless companies know enough to help law enforcement prosecute. Otherwise, their focus will be on vulnerabilities and remediation.

For governments, especially the United States, deterrence is a complicated work in progress. Surely, declaratory policy matters, and it is striking that the leaders of the United States were so much less forthright than German Chancellor Angela Merkel in warning Russia against election intervention. International law regards attacks that do physical damage as a causus belli, and in general it seems unwise to rule out horizontal escalation in retaliation for cyberattacks. In general, though, retaliation is likely to remain “naming and shaming” plus indictments, like those of special counsel Robert Mueller, that cannot be enforced but make the point. At the same time, while prospects looked much better several years ago, it surely makes sense, first, to agree with allies on rules of the road in cyberspace, then to try to engage Russia and China. The 2015 U.S.–China agreement not to do cyber espionage for commercial purposes is at least a start, one that has been emulated by a number of other countries in their dealings with China.

Finally, recent experience suggests some principles for responding to the threats in the cyber realm:

- Recognize that this is war by other means. Cyber and virtual conflict are the wars of the future, society against society.

- For companies in particular, but for all institutions, be clear that this is not an information technology problem. It cannot be left to the IT specialists. It is a “how we do our business” issue and thus must be very much on the desk of the CEO.

- So, too, it is everyone’s responsibility. Like the rest of us, the U.S. DNC was, in 2016, more interested in getting its work done than in protecting its networks. Its mistake made it easier for the Russians to hack into the emails of John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager.

- For companies, retaliation may be impossible, but it if is possible, it may be acceptable. Surely, there is a growing market of companies offering advice about how to retaliate. And the Macron’s campaigns flooding of pfishing emails is suggestive.

- For countries, the guidance is probably that of Hippocrates—do no harm. That probably applies especially to the United States, given its vulnerability. More often than is comfortable, it may have to emulate Lyndon Johnson’s line about the mule in the rain, just standing there and taking it. In any case, the great strength of the western democracies is their free media, and so the last thing they should want to do in retaliation is emulate Putin in ways that compromise or discredit those media engaged in telling true news, not fake.

- Finally, while autocracies, like Russia, have advantages in the cyber realm, shamelessness among them, they are hardly ten feet tall. The Russians were sloppy enough in both the American and French elections to raise the question: did they want us to know what they were doing, perhaps as a demonstration of their capability?

[1] This is adapted from a keynote presentation to a major cyber conference in Vilnius, Lithuania, in September 2018.